Like a lot of people who go way back in the land of food blogs, I learned how to make pad thai from Pim Techamuanvivit. Pim wrote Chez Pim for many years before moving onto make jams (still the best apricot I’ve ever had) and then, homesick for the food she missed from growing up in Bangkok and disappointed by the versions of Thai food she saw in American restaurants (and “the tyranny of peanut sauce”), opened her first restaurant, Kin Khao, in San Francisco in 2014. It received a Michelin star a year after it opened because why do anything mediocre?

But in 2007, she wrote a seminal post called Pad Thai For Beginners that I’ve read and reread so many times over the years, I’ve practically memorized it. As pad thai is one of the most popular street foods in Thailand, she encouraged us to approach it at home the way the street vendors do: the prep is already done, so you can finish it in a flash. First, she wants you to make the sauce in advance because the ingredients are not standardized — fish sauces and tamarind concentrates will vary in intensity between brands — and you’ll want to adjust as needed, not over a screaming hot pan while your noodles get soft. And she wants you to make extra because it keeps well, and then if your dish needs a little more oomph, you won’t have to run back to the fridge to measure more from bottles and jars. Finally, she wants us to never make more than two portions at once, which will lead to “clumps of oily, sticky noodles.” She explains that the textures and flavors of a proper pad thai “derive largely from the way the dish is cooked, that is to say its quick footloose dance in an ultra hot wok. That simply means you can’t do many servings at once.” This doesn’t mean you cannot feed a crowd, you simply prep as much as you’d need, but only cook a portion or two at a time.

So if I read this for the first time in 2007, why did it take me until 2018 to finally make it? Largely because the ingredients, depending on where you live, can be hard to get. While if it was simply a garnish here, you’d probably be fine without it, but something like tamarind isn’t a maybe ingredient in pad thai, it’s, in fact, one of the most essential flavors — providing the sour tang. Fish sauce is up there too (it makes things salty and nuanced). And, I’d argue, in descending order, bean sprouts (lightness and crunch), preserved radishes (a sweet/sour crunch), garlic chives, and palm sugar. And what took me so long to make it was trying to find a way to make peace with keeping the ingredients authentic* while finding swaps that might work if you’re a hundred miles from the nearest Thai grocery store.**

Eventually, though, my hunger for a recipe I could make when I craved it, which is weekly, won, which brings us up to today. Below is a recipe I mashed together from Pim, the dozen videos I found on YouTube of street vendors making pad thai (a very dangerous thing to do on an empty stomach), from Leela Punyaratabandhu’s excellent Simple Thai Food. And below that are a collection of suggestions of ingredients swaps I’ve pulled from the web. My biggest change: Hearkening back to my vegetarian days, I’ve always ordered pad thai with tofu (instead of the more traditional shrimp, or less traditional pork or chicken), and it’s the only way I crave it now. Maybe I’ll convert you too.

* The thing I noticed is that if you Google “pad thai recipe,” the first page of results has recipes that include fettuccine, bell peppers, peanut butter, honey, ketchup, napa cabbage, cilantro, butter, lemon, not to mention rice vinegar, soy sauce, Thai basil, mint, and more, which might sound closer to the region but aren’t actually typical in this. Does it matter? Does it matter that if I Googled it because I did, in fact, want to learn how to make it, that I’m unlikely to from these recipes? That maybe they’re delicious, but they’re not really pad thai? Of course, on this site, nary a recipe is devoutly aligned with the textbook version; I make changes based on personal taste, recipe ease, and more, and I do so here as well. But my roadmap, rules, have always been that I want to know the difference and to be able to talk about why I’m making the changes I have. It goes without saying that all of us can, and should, make the exact food we want to eat in the exact way that we want to make it, but also try to imagine how we might feel if someone told me they made our grandmother’s famous chicken soup recipe but they don’t use chicken or noodles and also changed all of the vegetables, they just call it our grandmother’s chicken soup. We’d say “wait, what?”

** I am not, and got almost everything I needed at Bangkok Center Grocery on Mosco Street; don’t miss the famous five-fried-dumplings-for-a-dollar (now $ 1.25) next door, and then go to Columbus Park and humiliate yourself on the pull-up bars, and marvel that Five Points (of Gangs In New York and also historical fame) is but an unrecognizable speck, or at least that’s my routine.

Previously

One year ago: Granola Bark

Two years ago: Potato Pizza, Even Better and Carrot Tahini Muffins

Three years ago: Obsessively Good Avocado Cucumber Salad and Strawberry Rhubarb Soda Syrup

Four years ago: Dark Chocolate Macaroons and Baked Eggs with Spinach and Mushrooms

Five years ago: Bee Sting Cake

Six years ago: Banana Bread Crepe Cake with Butterscotch

Seven years ago: Blackberry and Coconut Macaroon Tart

Eight years ago: Almond Macaroon Torte with Chocolate Frosting, Tangy Spiced Brisket, andNew York Cheesecake

Nine years ago: Chocolate Caramel Crackers

Ten years ago: Chicken with Almonds and Green Olives, Shaker Lemon Pie and Spring Panzanella

Eleven years ago: The Tart Marg

And for the other side of the world:

Six Months Ago: Sausage and Potato Roast with Arugula

1.5 Years Ago: Garlic Wine and Butter Steamed Clams

2.5 Years Ago: My Old-School Baked Ziti

3.5 Years Ago: Better Chicken Pot Pies

4.5 Years Ago: Fudgy Chocolate Sheet Cake

Cripsy Tofu Pad Thai

- 6 ounces firm or extra-firm tofu (not silken)

- 5 ounces dried rice noodles (sticks), about 1/8-inch (3mm) wide

- 2 tablespoons fish sauce, regular (not vegetarian) or vegetarian, plus more to taste

- 2 tablespoons tamarind concentrate, plus more to taste

- 2 to 4 teaspoons dark brown sugar, plus more to taste

- A pinch or two Thai or other chile flakes or chili powder, or a shot of Sriracha

- Vegetable, grapeseed or another neutral, high-heat cooking oil, plus more as needed

- 1 small shallot, chopped (optional)

- 2 garlic cloves, chopped

- 2 tablespoons sweet preserved radish, grated or minced

- 2 handfuls (about 1 cup, although it’s awkward to measure in cups) bean sprouts, plus more for garnish

- 1 large egg

- 4 garlic chives, or the green parts of 8 scallions or spring onions, cut into 2-inch pieces, divided

- Additional Thai or other chile flakes or chili powder

- Remaining garlic chives and bean sprouts

- 2 large lime wedges

- 2 tablespoons crushed roasted peanuts, salted or unsalted

Garnishes

Prepare noodles: Meanwhile, place noodles in a large bowl; pour hot water over to cover. Don’t worry if they break a little; shorter noodles (even 6″ lengths) are common for pad thai. Let it soak for 10 minutes, after which they should be pliable but too al dente to enjoy without further cooking; longer soaks will turn the noodles mushy in the pan. Drain and set noodles aside.

Prepare the sauce: Stir together fish sauce, tamarind, brown sugar, and chili powder. Taste and adjust the flavor balance until it suits you, and it will almost certainly require some adjusting because ingredient intensity varies between brands. Ideally you’re looking for something salty followed by a mild sourness, a little sweetness, and a little lick of heat. You will add more heat and acidity at the end. Set this aside.

Crisp the tofu: Heat a large frying pan or a wok over high for a full minute, then add a tablespoon or two of oil and let this heat for a full minute too, and then add tofu cubes. Reduce heat to medium-high. Cook them until browned underneath, then use a thin spatula to turn them and cook some more, until all sides are golden and crisp. Drain on paper towels, and season while hot with a little salt and chili powder, to taste.

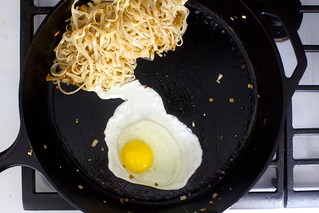

Cook the pad thai: Add another generous glug oil to the hot pan and, once very hot, cook garlic, shallots, and radishes for a minute, until they take on a little edge of color. Add noodles and sauce and cook until noodles absorb sauce, if needs longer to soften (you can use the edge of your spatula to try to cut them to get an idea if it’s still too firm), you can add 2 tablespoons water at a time until they’re fully cooked. You can break your noodles into shorter chunks, if you desire, with your spatula. Add half your bean sprouts and garlic chives (reserving the rest for garnishes) and toss to combine.

Push to the side, add crack your egg into empty part of pan. When halfway cooked, start scrambling, then mix into noodles. Add crispy tofu back to pan now, and toss to combine. Transfer to plate.

To finish: Around the rim, leave extra garnishes in a little piles. Squeeze lime juice over before eating (it really wakes it up).

Tamarind: This is the sticky brown acidic pulp from the pod of a tree of the pea family — it provides the signature faint sourness of pad thai. It comes in paste, and concentrate; I used the latter. Paste is the most common. To use it, reconstitute 1 part of the paste in 2 parts of water, and stir until combined. Typically, people add water to tamarind concentrate as well to use it in recipes, but I’m having us add water to the pan as needed to cook the noodles instead. Some people don’t like the intensity of tamarind. Pim says that if this is you, you use less and add white vinegar. Other swaps I’ve seen suggested online: a mixture of lime juice and brown sugar; a dab of ketchup (look, I’m just reporting here!) plus lime juice or plain vinegar.

Using other proteins: Almost all pad thai, even the most common with shrimp, has some tofu in it, usually a couple of tablespoons pressed tofu that comes in small blocks, which you can find at many Asian grocery stores. Here I’m calling for firm or extra-firm, which come in water and are easier to find, and making it the star of the show. If you’d like to use shrimp here instead, I’d estimate 6 medium fresh shrimp, peeled and deveined, per serving, and you can par-cook it with the garlic, shallot, and radish in the beginning. Don’t fully cook it, it will finish with the noodles and sauce over the next few minutes. If you’d like to use chicken or pork, I’d estimate 2 ounces, chopped in rough chunks, per serving, and cook is as you would the shrimp. Want to use none of the above? An extra egg might give your pad thai all the protein you wish for. Finally, quite often, the egg is cooked along with the shrimp in the beginning but I prefer mine added closer to the end so it’s a bit more present.

Eggs: Are optional in pad thai. In Thailand, they’ll ask you when you order it whether or not you want it. Sometimes it is scrambled in, other times a paper-thin omelet is poured made and the pad thai is wrapped inside it, like a crepe. I’ll save that for Pad Thai for Intermediates.

Palm sugar: Is the standard sweetener in pad thai, not brown sugar, but on this, I defaulted to what was already in my pantry. I think coconut sugar could be a good swap too. Palm sugar often comes in semi-solid blocks; you’ll want to scrape some off and warm it in the microwave or over another heat and it will loosen. For pad thai sauce, cooks will often melt the palm sugar in a pan and add the other sauce ingredients, just to warm them until liquefied. For palm sugar, you’ll want to use a bit more for the same level of sweetness; I’d use 3 teaspoons for every 2 here, but of course you’ll adjust this to taste too. Finally, palm sugar these days can be purchased in granulated form.

Fish sauce: Is salty and a little funky, and is the magic ingredient is so many of our favorite dishes. Between brands and even countries where its manufactured, saltiness and funkiness vary a lot. Vietnamese fish sauce is usually considered sweeter/less salty than Thai. Red Boat is one of the most popular; I had MegaChef and Squid brands around — the latter is probably the strongest/saltiest I tried. I haven’t tested it out, but vegetarian fish sauce is available. Here is a brand with good reviews; it sounds like you’ll want to use more to get the same intensity.

Sweet preserved radish: This provides a unique chewy sour/salty sweet flavor throughout in slightly crunchy bits I really enjoy it here, but I do think your pad thai can still taste good without it, you just might find you need a little more of the other sweet ingredients, such as tamarind and palm or brown sugar.

Shallots: I only spotted these in a minority of the recipes I perused, but made mine with and without them, and liked them here. I felt that the cooked shallot + pad thai sauce faintly reminded me of the preserved radish flavor, too, so definitely worth including if you can’t find the radishes. If you don’t have a shallot and are using the green part of scallions instead of garlic chives, might you use the white parts as you’d use the shallot here? Oh, I like the way you think.

Bean sprouts: Are crunchy and fantastic here. If you can’t find or get them, I bet shredded white cabbage or very thin juliennes of napa cabbage might provide a similarly refreshing crunch. I’d barely cook them.

Source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/smittenkitchen/~3/C03WoHX5qH8/